ZKML EZKL MNIST Lab: Verifiable Inference, Quantization, and the Prover Memory Wall

TL;DR — I wanted a hands-on, reproducible sense of what verifiable inference costs in practice:

- Can I produce a proof that a fixed model ran inference on a private input and produced a public output?

- What are the real artifacts and costs: PK/VK sizes, prove time, verify time, proof size?

- Where does it break on consumer hardware (spoiler: prover memory)?

Repo:

https://github.com/reymom/zkml-ezkl-mnist-lab

0. What this project is (and what it is not)

This is verifiable inference, not training:

- Given a fixed ONNX model

M, I generate a ZK proof that a private inputxproduces a public outputy = M(x)under EZKL’s quantized (fixed-point style) circuit settings (scale, logrows, etc.). In this lab,yis the model’s 10-dimensional output vector (logits); the predicted class (argmax) is derived outside the circuit. - The proof certifies correct execution of the quantized computation (the circuit). It does not prove anything about data provenance, training correctness, or whether the prediction is semantically “right.”

What it does not try to do:

- Prove training, model selection, or dataset provenance.

- Ship a production onchain verifier or end-to-end ZKML product.

- Make claims about robustness or “trustworthy AI.”

1. Background: why ZKML is its own engineering problem

ML inference graphs are built for floating point. SNARK circuits are built for deterministic arithmetic over finite fields. ZKML toolchains bridge that gap by compiling an inference graph into an arithmetic-friendly representation (fixed-point style quantization, range checks, lookups, etc.) and then proving correct evaluation.

In this lab I use EZKL, which compiles ONNX graphs into circuits and proves them using a Halo2-based backend.

2. Pipeline (reproducible)

- Train a small CNN on MNIST in PyTorch

- Export ONNX (opset 13, static input shape 1×1×28×28)

ezkl gen-settings→ezkl calibrate-settings(optional, but informative)ezkl compile-circuitezkl get-srsezkl setup(generate VK/PK)ezkl gen-witness→ezkl prove→ezkl verify

One practical gotcha: EZKL calibration expects input_data as flattened vectors ([batch][flat]), so I convert the NCHW tensor into input_flat.json.

Reproduce: exact commands

Train + export ONNX:

python scripts/train_export_mnist_cnn.py --epochs 1 --limit-train 20000 --limit-test 5000

python - <<'PY'

import onnx

m = onnx.load("models/mnist_cnn.onnx")

print("ir_version:", m.ir_version)

print("opsets:", [(o.domain, o.version) for o in m.opset_import])

PYGenerate settings + calibrate (note: calibration expects flattened inputs):

cd artifacts

ezkl gen-settings -M ../models/mnist_cnn.onnx

cp settings.json settings.precal.json

cd ..

python - <<'PY'

import json, numpy as np

from pathlib import Path

j = json.load(open("data/input.json"))

x = np.array(j["input_data"], dtype=np.float32).reshape(-1).tolist()

Path("data/input_flat.json").write_text(json.dumps({"input_data": [x]}))

print("wrote data/input_flat.json; flat_len =", len(x))

PY

cd artifacts

ezkl calibrate-settings \

--data ../data/input_flat.json \

--model ../models/mnist_cnn.onnx \

--settings-path settings.json \

--target resourcesNote: setup takes only the compiled circuit because the settings (including logrows) are baked into the .ezkl file produced by compile-circuit.

Option A: Compile + setup (calibrated circuit — may OOM on laptops):

cd artifacts

ezkl compile-circuit --model ../models/mnist_cnn.onnx --settings-path settings.json --compiled-circuit mnist_cnn.ezkl

ezkl get-srs --settings-path settings.json

ezkl setup -M mnist_cnn.ezkl --pk-path pk.key --vk-path vk.keyOption B: Compile + setup (smaller circuit that fits my laptop):

cd artifacts

ezkl get-srs --settings-path settings.precal.json

ezkl compile-circuit --model ../models/mnist_cnn.onnx --settings-path settings.precal.json --compiled-circuit mnist_cnn_small.ezkl

ezkl setup -M mnist_cnn_small.ezkl --pk-path pk.small.key --vk-path vk.small.keyProve & verify (small circuit):

cd artifacts

time ezkl gen-witness -M mnist_cnn_small.ezkl -D ../data/input_flat.json

time ezkl prove -M mnist_cnn_small.ezkl --witness witness.json --pk-path pk.small.key --proof-path proof.small.pf --check-mode unsafe

time ezkl verify --proof-path proof.small.pf --vk-path vk.small.key --settings-path settings.precal.jsonONNX → EZKL operator table (sanity + transparency)

EZKL can print an operator table for the compiled ONNX graph. This is useful both as a sanity check (shapes/scales) and as a “what is this circuit actually doing?” artifact.

mkdir -p artifacts

ezkl table -M models/mnist_cnn.onnx | tee artifacts/onnx_table.txtExample excerpt (first layers):

idx opkind out_scale out_dims

0 Input 7 [1, 1, 28, 28]

3 CONV (...) 7 [1, 8, 28, 28]

5 LEAKYRELU (slope=0) 7 [1, 8, 28, 28]

6 MaxPool (...) 7 [1, 8, 14, 14]

9 CONV (...) 7 [1, 16, 14, 14]

11 MaxPool (...) 7 [1, 16, 7, 7]

12 RESHAPE (shape=[1, 784]) 7 [1, 784]

...(Full table: artifacts/onnx_table.txt.)

3. Results: the two configurations that mattered

The most useful outcome of this “small lab” was not a fancy model — it was an empirical boundary: numerical fidelity improvements can push proving beyond consumer hardware limits.

A) Provable configuration (fits my laptop)

Using the smaller, pre-calibration settings:

- settings:

input_scale=7, param_scale=7, logrows=17(artifacts/settings.precal.json) - witness generation: ~0.5s

- proving key load: ~21.8s

- proof generation: ~89.7s (wall ~112s)

- verification: ~0.8s (

verified=true) - artifact sizes:

- compiled circuit: 1.8MB

- proving key: 3.5GB

- verification key: 1.5MB

- witness: 110KB

- proof: 82KB

Note: proving “wall time” includes loading the proving key from disk; the internal “proof took …” log excludes that I/O.

mnist_cnn_small.ezkl: 1.8M

pk.small.key: 3.5G

vk.small.key: 1.5M

witness.json: 110K

proof.small.pf: 82KB) Calibrated configuration (hits the memory wall)

After ezkl calibrate-settings --target resources:

- settings:

input_scale=13, param_scale=13, logrows=20 - calibration fidelity report (example): mean_abs_error ≈ 0.00110, max_abs_error ≈ 0.00253

- proving: OOM-killed on my machine (RSS hit ~12.6GB before the kernel killed the process)

To confirm it was a real memory wall (not a silent crash), the kernel OOM killer reported:

Out of memory: Killed process ... (ezkl) ... anon-rss: ~12645104kBIn other words: calibration improved numerical fidelity, but pushed the prover memory footprint beyond what this machine can sustain.

4. The cryptographer insight: proofs certify computation, not truth

A ZK proof here answers: “did the circuit compute ?”

It does not answer: “is y correct?”

To make that explicit, I proved a naturally misclassified MNIST sample:

- found sample:

idx=18, label3, prediction5{"idx": 18, "label": 3, "pred": 5} - proved inference anyway under the same small circuit (

logrows=17) - proof generation: ~78.5s

- proof size: 82KB

The proof verifies because the system is doing exactly what it claims: verifiable computation.

5. What I’d benchmark next (if I had more compute/time)

A real benchmark suite would automate a parameter sweep and emit a CSV like:

Scale, Logrows, PK Size, Proof Size, Prove Time, Verify Time, (Optional) Quantized Accuracy

But even this minimal lab already surfaces the dominant practical constraint: key sizes and prover memory dominate quickly, and “better quantization fidelity” can be expensive.

References

- EZKL repository: https://github.com/zkonduit/ezkl

- EZKL docs (setup/prove/verify): https://docs.ezkl.xyz/

- EZKL benchmark write-up: https://blog.ezkl.xyz/post/benchmarks/

- EZKL nanoGPT / larger-model discussion: https://blog.ezkl.xyz/post/nanogpt/

- ONNX (model interchange format): https://onnx.ai/

- Halo2 proving system: https://github.com/privacy-scaling-explorations/halo2

- Freivalds’ algorithm (matrix multiplication check): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freivalds%27_algorithm

Appendix: why Freivalds shows up in “verifiable linear algebra” discussions

This lab uses a SNARK-based prover/verifier (EZKL/Halo2). Freivalds is not used inside EZKL’s proving system.

So why include it at all?

Because the dominant cost center in ZKML is linear algebra (GEMMs / convs / tensor ops), and there is a parallel design space of verifiable computation for linear algebra that relies on randomized checking rather than a full SNARK. Freivalds is the canonical “hello world” for that world: it shows how verification can be O(n²) instead of O(n³) for matrix multiplication, with a tunable soundness error via repetitions.

Small micro-lab

In ZKML, linear layers dominate cost; SNARK systems prove them inside the circuit, but many protocols exploit linear structure with specialized verification tricks—Freivalds is the simplest example of that design space.

I implemented a tiny Freivalds checker to keep the intuition concrete:

python scripts/freivalds.pyOutput on my machine:

n=256

naive check good: True time=0.0378s

freivalds good : True time=0.0018s (k=10)

freivalds bad : False time=0.0005s (k=10)Takeaway: even though EZKL is a SNARK pipeline, ZKML sits on top of linear algebra, and many systems (and papers) exploit linear structure with specialized verification ideas. This appendix is here to anchor that intuition with a runnable artifact.

Stay Updated

Get notified when I publish new articles about Web3 development, hackathon experiences, and cryptography insights.

You might also like

Crescent Bench Lab: Measuring ZK Presentations for Real Credentials (JWT + mDL)

A small Rust lab that vendors microsoft/crescent-credentials, generates Crescent test vectors, and benchmarks zksetup/prove/show/verify across several parameters — including proof sizes and selective disclosure variants.

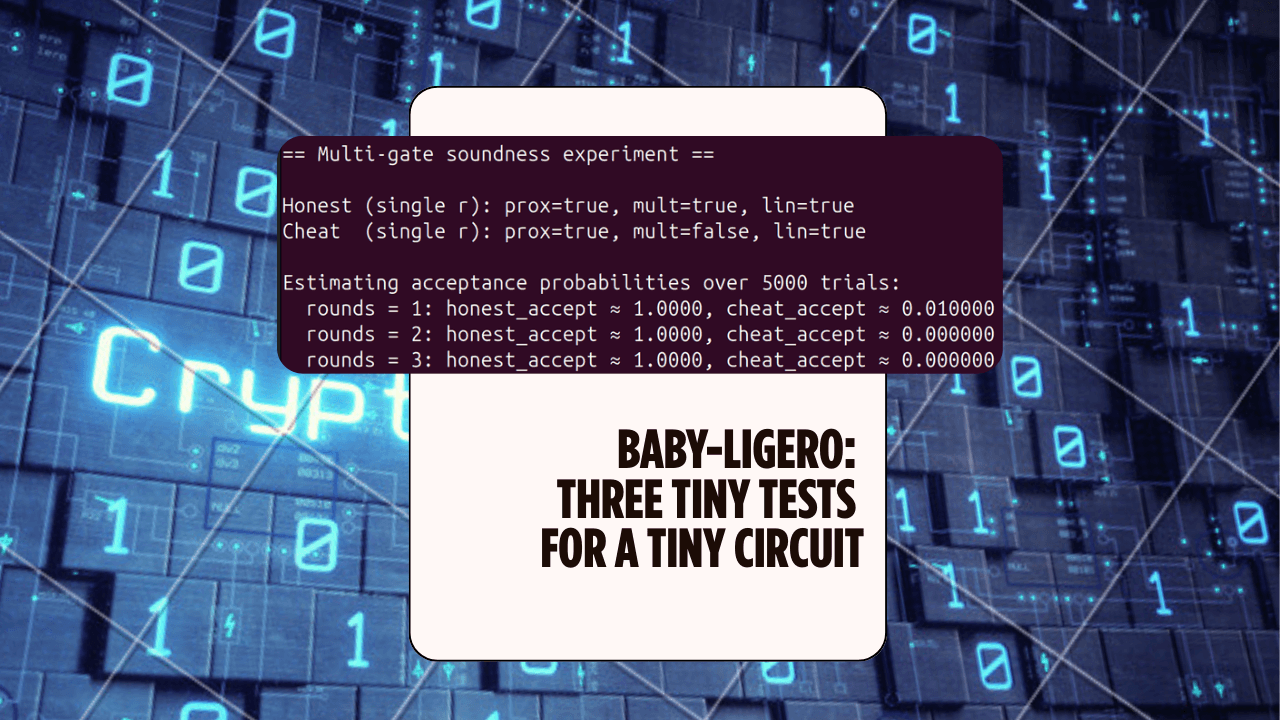

Baby-Ligero: Three Tiny Tests for a Tiny Circuit — ZK Hack S3M5

A mini Rust lab that implements a baby version of Ligero's three tests — proximity, multiplication, and linear — for a tiny arithmetic circuit, and uses them to see soundness amplification in action.

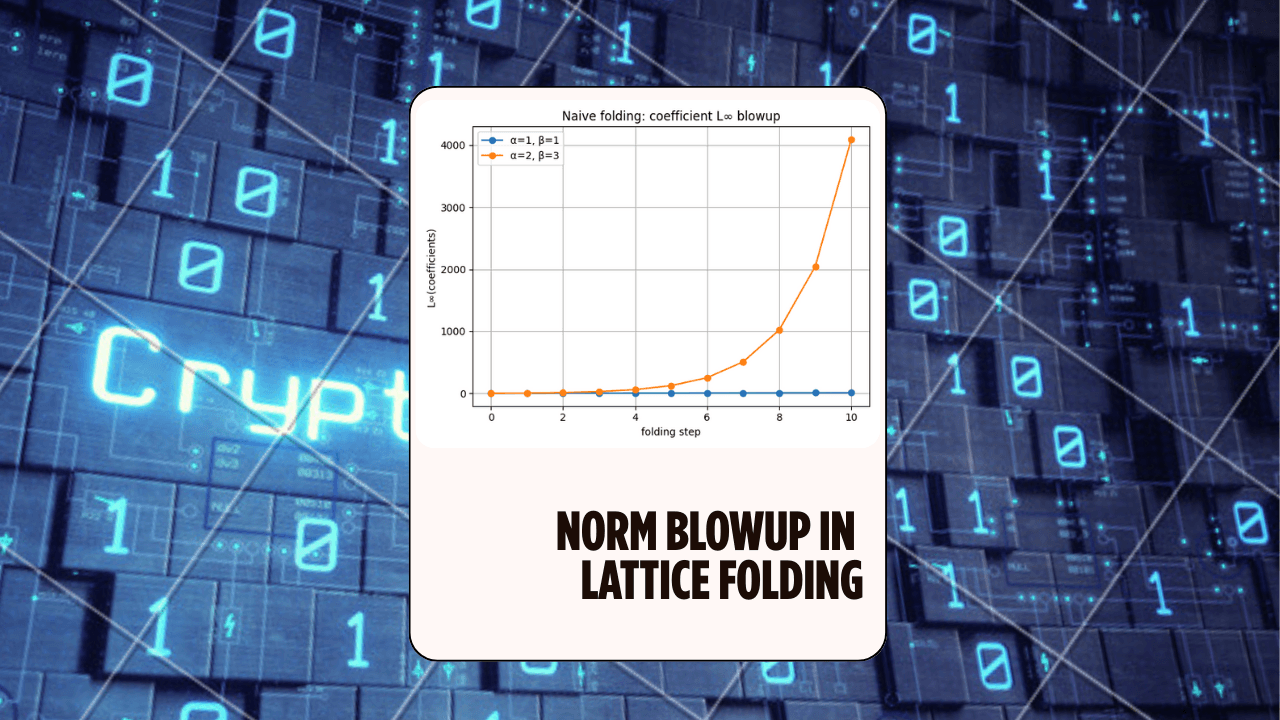

Norm Blowup in Lattice Folding (LatticeFold Lab) — ZK Hack S3M4

A hands-on Rust experiment exploring why folding causes norm blowup in lattice commitments, and how decomposition keeps the digits small — the core idea behind LatticeFold and LatticeFold+.