Norm Blowup in Lattice Folding (LatticeFold Lab) — ZK Hack S3M4

TL;DR — I took Binyi Chen's LatticeFold whiteboard session (ZK Hack S3M4) and turned the main intuition into a tiny Rust lab:

- Model lattice witnesses as small integer vectors.

- Apply a folding step

s' = α·s + β·tand watch L∞ norms explode.- Decompose each blown-up vector in base 4/8/16 and track the digit L∞.

- See experimentally that:

- coefficients grow roughly exponentially;

- digits stay tiny, which is exactly what LatticeFold range proofs exploit.

All the code in this post comes from a small norm-blowup playground I built for this week's study session.

1. Motivation

In week 4 of my structured ZK learning (based on the ZK Hack Whiteboard Sessions), I watched Binyi Chen's LatticeFold intervention.

The bit that stuck is extremely simple and extremely important:

Folding is linear. Linear recurrences grow.

Lattice proofs require “small secrets”.

→ We must somehow keep smallness under control.

In lattice-based SNARKs we commit to short vectors and then apply folding schemes to batch or recurse proofs. Over time, folding mixes the witness with random challenges and other vectors — and the norms just blow up.

LatticeFold's trick is to decompose the big coefficients into small base-B digits, and prove range bounds on the digits, not on the raw coefficients.

This post is a small Rust lab to see that phenomenon numerically.

2. Setup

I stayed as close as possible to the SIS lab from the previous week:

-

work with integer vectors in ,

-

sample short vectors with coefficients in ,

-

define a folding step

where is another fixed short vector in the same trial.

At each step we measure:

- L₂ norm ,

- L∞ norm ,

- how many coordinates exceed the original bound ,

- and, after decomposition, the digit L∞ for bases 4, 8 and 16.

3. Small Integer Lattice Vectors

Below is the minimal element.rs module used throughout this experiment:

use anyhow::{anyhow, Result};

use rand::Rng;

/// Lattice-style vector with integer coefficients.

pub type Element = Vec<i32>;

#[derive(Clone, Copy)]

pub enum ElementLength {

N64,

N128,

}

impl ElementLength {

pub fn length(&self) -> usize {

match self {

ElementLength::N64 => 64,

ElementLength::N128 => 128,

}

}

}

#[derive(Clone, Copy)]

pub struct ElementParams {

pub n: ElementLength,

pub bound: i32, // coefficients in [-bound, bound]

}

/// Sample a "small" vector with coefficients in [-bound, bound].

pub fn generate_small_element(p: ElementParams) -> Result<Element> {

if p.bound <= 0 {

return Err(anyhow!("bound must be positive"));

}

let mut rng = rand::rng();

let mut v = Vec::with_capacity(p.n.length());

for _ in 0..p.n.length() {

v.push(rng.gen_range(-p.bound..=p.bound));

}

Ok(v)

}

/// Integer linear combination: s' = alpha * s1 + beta * s2.

pub fn linear_combination(s1: &Element, s2: &Element, alpha: i32, beta: i32) -> Result<Element> {

if s1.len() != s2.len() {

return Err(anyhow!("elements have different size"));

}

Ok(s1

.iter()

.zip(s2)

.map(|(&a, &b)| alpha * a + beta * b)

.collect())

}

/// L2 norm as f64, for measuring growth.

pub fn l2_norm(vector: &[i32]) -> f64 {

let sum_sq: f64 = vector.iter().map(|&x| (x as f64).powi(2)).sum();

sum_sq.sqrt()

}

/// L∞ norm: max |coord|.

pub fn linf_norm(vector: &[i32]) -> i32 {

vector.iter().map(|x| x.abs()).max().unwrap_or(0)

}

/// Count how many coordinates exceed the bound B.

pub fn count_exceeding(vector: &[i32], bound: i32) -> usize {

vector.iter().filter(|&&x| x.abs() > bound).count()

}This already lets us simulate witness blowup.

4. Toy Decomposition (Base-B Digits)

In LatticeFold, the prover doesn't try to keep the raw coefficients small. Instead, every coefficient is written as a signed base-B expansion:

Here is the minimal code I used:

/// Signed base-B decomposition of a single coefficient, with small digits.

pub fn decompose_coeff(mut c: i32, base: i32) -> Vec<i32> {

assert!(base >= 2);

let mut digits = Vec::new();

while c != 0 {

let mut rem = c.rem_euclid(base);

if rem > base / 2 {

rem -= base; // signed digit in [-base/2, base/2]

}

digits.push(rem);

c = (c - rem) / base;

}

if digits.is_empty() {

digits.push(0);

}

digits

}

/// Decompose each coefficient and flatten all digits.

pub fn decompose_element(e: &Element, base: i32) -> Vec<i32> {

let mut all = Vec::new();

for &c in e {

all.extend(decompose_coeff(c, base));

}

all

}Even when becomes huge, the digits of this signed representation stay in a tiny interval (e.g. for base 4). That's exactly what we'll track in the experiment.

5. Folding Experiment

The folding lab is in folding.rs. The configuration describes:

- vector length

n, - initial bound

B(we useB = 1), - folding coefficients

α,β, - number of folds and trials,

- and the list of bases we want to test.

use crate::element::*;

use anyhow::Result;

/// Configuration for a folding experiment.

#[derive(Clone, Copy)]

pub struct FoldingConfig {

pub length: ElementLength,

pub bound: i32,

pub alpha: i32,

pub beta: i32,

pub num_folds: usize,

pub num_trials: usize,

/// Bases used for decomposition, e.g. &[4, 8, 16].

pub decomp_bases: &'static [i32],

}

/// Aggregated stats per folding step (averaged over trials).

pub struct FoldStats {

pub step: usize,

pub avg_l2: f64,

pub avg_linf: f64,

pub avg_exceeding: f64,

/// One digit-L∞ per base, same order as `decomp_bases`.

pub avg_decomp_linf: Vec<f64>,

}Then, the experiment:

pub fn run_experiment(cfg: FoldingConfig) -> Result<Vec<FoldStats>> {

let n_steps = cfg.num_folds + 1;

let nbases = cfg.decomp_bases.len();

let mut sum_l2 = vec![0.0f64; n_steps];

let mut sum_linf = vec![0.0f64; n_steps];

let mut sum_exceed = vec![0.0f64; n_steps];

let mut sum_decomp_linf = vec![vec![0.0f64; n_steps]; nbases];

for _trial in 0..cfg.num_trials {

let params = ElementParams { n: cfg.length, bound: cfg.bound };

let mut s: Element = generate_small_element(params)?;

let t: Element = generate_small_element(params)?;

for step in 0..n_steps {

accumulate_step_stats(

step,

&s,

cfg.bound,

cfg.decomp_bases,

&mut sum_l2,

&mut sum_linf,

&mut sum_exceed,

&mut sum_decomp_linf,

);

if step < cfg.num_folds {

s = crate::element::linear_combination(&s, &t, cfg.alpha, cfg.beta)?;

}

}

}

let trials = cfg.num_trials as f64;

let mut stats = Vec::with_capacity(n_steps);

for step in 0..n_steps {

let mut avg_decomp = Vec::with_capacity(nbases);

for bi in 0..nbases {

avg_decomp.push(sum_decomp_linf[bi][step] / trials);

}

stats.push(FoldStats {

step,

avg_l2: sum_l2[step] / trials,

avg_linf: sum_linf[step] / trials,

avg_exceeding: sum_exceed[step] / trials,

avg_decomp_linf: avg_decomp,

});

}

Ok(stats)

}

fn accumulate_step_stats(

step_idx: usize,

v: &Element,

bound: i32,

decomp_bases: &[i32],

sum_l2: &mut [f64],

sum_linf: &mut [f64],

sum_exceed: &mut [f64],

sum_decomp_linf: &mut [Vec<f64>],

) {

let l2 = l2_norm(v);

let linf = linf_norm(v);

let exceeding = count_exceeding(v, bound) as f64;

sum_l2[step_idx] += l2;

sum_linf[step_idx] += linf as f64;

sum_exceed[step_idx] += exceeding;

for (bi, &base) in decomp_bases.iter().enumerate() {

let digits = decompose_element(v, base);

let d_linf = linf_norm(&digits);

sum_decomp_linf[bi][step_idx] += d_linf as f64;

}

}The main.rs runs two configurations:

- a mild folding step:

s' = s + t(α = 1, β = 1), - an aggressive one:

s' = 2s + 3t(α = 2, β = 3),

always with n = 64, B = 1, and bases [4, 8, 16].

mod element;

mod folding;

use element::ElementLength;

use folding::{run_experiment, FoldingConfig};

fn main() {

let bases: &[i32] = &[4, 8, 16];

let configs = vec![

FoldingConfig {

length: ElementLength::N64,

bound: 1,

alpha: 1,

beta: 1,

num_folds: 10,

num_trials: 200,

decomp_bases: bases,

},

FoldingConfig {

length: ElementLength::N64,

bound: 1,

alpha: 2,

beta: 3,

num_folds: 10,

num_trials: 200,

decomp_bases: bases,

},

];

for cfg in configs {

let stats = run_experiment(cfg).expect("experiment failed");

let bases_str = cfg

.decomp_bases

.iter()

.map(|b| b.to_string())

.collect::<Vec<_>>()

.join(",");

let decomp_cols_header = cfg

.decomp_bases

.iter()

.map(|b| format!("avg_decomp_linf_b{}", b))

.collect::<Vec<_>>()

.join(", ");

println!(

"# Folding experiment: n = {}, bound = {}, alpha = {}, beta = {}, folds = {}, trials = {}, bases = [{}]",

cfg.length.length(),

cfg.bound,

cfg.alpha,

cfg.beta,

cfg.num_folds,

cfg.num_trials,

bases_str,

);

println!(

"# step, avg_l2, avg_linf, avg_exceeding_coeffs, {}",

decomp_cols_header

);

for s in stats {

let decomp_values = s

.avg_decomp_linf

.iter()

.map(|v| format!("{:>8.2}", v))

.collect::<Vec<_>>()

.join(", ");

println!(

"{:>2}, {:>12.4}, {:>8.2}, {:>8.2}, {}",

s.step, s.avg_l2, s.avg_linf, s.avg_exceeding, decomp_values

);

}

println!();

}

}Running with cargo run --release > plots/data.txt gives the dataset for plotting.

6. Results

For α = 1, β = 1 we get:

# Folding experiment: n = 64, bound = 1, alpha = 1, beta = 1, folds = 10, trials = 200, bases = [4,8,16]

# step, avg_l2, avg_linf, avg_exceeding_coeffs, avg_decomp_linf_b4, avg_decomp_linf_b8, avg_decomp_linf_b16

0, 6.5509, 1.00, 0.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00

1, 9.2229, 2.00, 14.24, 2.00, 2.00, 2.00

2, 14.5865, 3.00, 28.41, 2.00, 3.00, 3.00

3, 20.6409, 4.00, 42.81, 2.00, 4.00, 4.00

4, 26.9225, 5.00, 42.81, 1.00, 4.00, 5.00

5, 33.3028, 6.00, 42.81, 2.00, 4.00, 6.00

6, 39.7340, 7.00, 42.81, 2.00, 3.00, 7.00

7, 46.1950, 8.00, 42.81, 2.00, 2.00, 8.00

8, 52.6747, 9.00, 42.81, 2.00, 1.00, 8.00

9, 59.1670, 10.00, 42.81, 2.00, 2.00, 8.00

10, 65.6681, 11.00, 42.81, 2.00, 3.00, 7.00For α = 2, β = 3 we get an aggressive blowup:

# Folding experiment: n = 64, bound = 1, alpha = 2, beta = 3, folds = 10, trials = 200, bases = [4,8,16]

# step, avg_l2, avg_linf, avg_exceeding_coeffs, avg_decomp_linf_b4, avg_decomp_linf_b8, avg_decomp_linf_b16

0, 6.5449, 1.00, 0.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00

1, 23.3235, 5.00, 42.17, 2.00, 3.00, 5.00

2, 63.7961, 13.00, 56.83, 2.00, 4.00, 7.00

3, 145.6572, 29.00, 56.83, 2.00, 4.00, 8.00

4, 309.6519, 61.00, 56.83, 2.00, 4.00, 4.00

5, 637.7499, 125.00, 56.83, 2.00, 4.00, 8.00

6, 1293.9949, 253.00, 56.83, 2.00, 4.00, 8.00

7, 2606.5081, 509.00, 56.83, 2.00, 4.00, 8.00

8, 5231.5459, 1021.00, 56.83, 2.00, 4.00, 4.00

9, 10481.6271, 2045.00, 56.83, 2.00, 4.00, 8.00

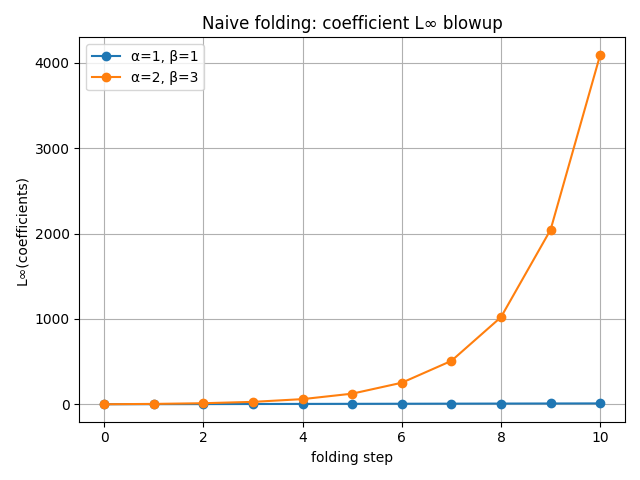

10, 20981.7923, 4093.00, 56.83, 2.00, 4.00, 8.00(1) Coefficient norms blow up

Even from tiny secrets, folding produces an exponential-looking L∞ curve.

Example (from my runs):

1 → 5 → 13 → 29 → 61 → 125 → …This is the reason naive folding breaks soundness: too many coefficients exceed the bound.

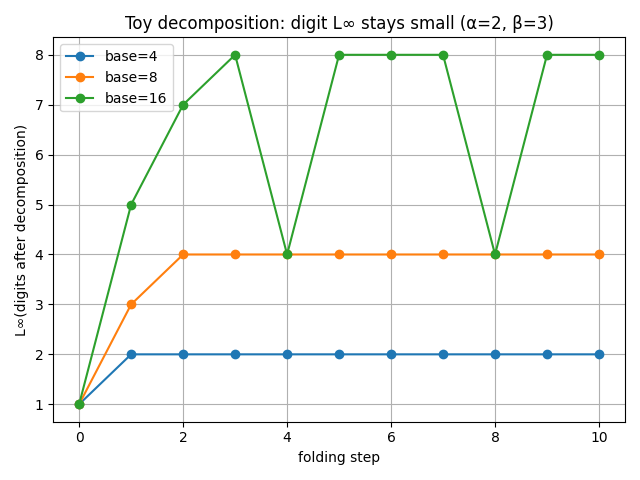

(2) Digit norms stay tiny

But after decomposition:

- base 4 → digits in [-2,2],

- base 8 → digits in [-4,4],

- base 16 → digits in [-8,8].

No matter how large the original coefficients become, their digits stay tiny and bounded.

This is the core insight behind LatticeFold and LatticeFold+:

you only need to prove bounds on the digits, not on the giant raw coefficients.

(3) Multi-base comparison

Here is where the plot becomes meaningful:

- base 4: digit L∞ ≈ 2

- base 8: digit L∞ ≈ 4

- base 16: digit L∞ ≈ 8

They are flat because decomposition is literally designed to clamp digit magnitude, but the rising height across bases shows the tradeoff:

- small base = more digits, smaller digit bound

- large base = fewer digits, larger digit bound

Visually: the flat lines are different horizontal layers → simple to explain and pretty.

Let's look at the plots.

7. Plots: Blowup vs Decomposition

First, the coefficient norms:

- The blue curve (

α=1, β=1) grows linearly in this small regime. - The orange curve (

α=2, β=3) shoots up into the thousands by step 10.

This is the “folding causes norm blowup” story in one picture.

Now the decomposition side:

- Base 4 (blue): digit L∞ stays around ≈ 2.

- Base 8 (orange): digit L∞ stabilizes around ≈ 4.

- Base 16 (green): digit L∞ floats around ≈ 7–8.

Even though the underlying coefficients hit values like 4093, their digits remain tiny and bounded. This is precisely what LatticeFold leverages: range proofs over digits, not over the raw coefficients.

The multi-base comparison also shows the tradeoff:

- smaller base ⇒ more digits but smaller digit bound;

- larger base ⇒ fewer digits but larger digit bound.

In a real protocol you balance these against proof size and performance.

8. Interpretation and Takeaways

For me, this little experiment locked in three key ideas from Binyi Chen's talk:

-

Folding inevitably causes norm blowup. The recurrence is a linear dynamical system. Unless α and β are trivial, both L₂ and L∞ norms grow quickly, and soon almost every coordinate violates the “smallness” bound we started with.

-

Decomposition is how lattice proofs recover smallness. Instead of proving that the blown-up coefficient itself is small, you decompose it into base-B digits and prove that each digit lies in a small range. The experiment shows exactly that: digit L∞ stays essentially flat while coefficient L∞ explodes.

-

Multi-base decomposition is a tunable design space. Different bases give different constant digit bounds. In LatticeFold and LatticeFold+ this becomes part of the engineering trade-off between proof size, verifier time, and norm margins.

This week's lab is small — just integer vectors, a simple folding recurrence, and a toy range check on digits — but it gives me a concrete mental model for the “norm management” problem in lattice SNARKs.

With a bit more time I would like to have done more:

- move this toy into an actual polynomial ring setting,

- and connect it more directly with the LatticeFold and LatticeFold+ papers.

9. References and Further Reading

- Talk — ZK Hack S3M4: LatticeFold, w/ Binyi Chen

- Paper — LatticeFold: A Lattice-based Folding Scheme and its Applications to Succinct Proof Systems, Boneh & Chen (2024), ePrint 2024/257.

- Update — LatticeFold+: Faster, Simpler, Shorter Lattice-Based Folding for Succinct Proof Systems, Binyi Chen (zkSummit13 talk).

- Background:

- SWIFFT: A Modest Proposal for FFT Hashing — Lyubashevsky, Micciancio, Peikert, Rosen.

- SoK: Zero-Knowledge Range Proofs — Christ et al., ePrint 2024/430.

- LaBRADOR: Compact Proofs for R1CS from Module-SIS — Beullens & Seiler, ePrint 2022/1341.

Stay Updated

Get notified when I publish new articles about Web3 development, hackathon experiences, and cryptography insights.

You might also like

Crescent Bench Lab: Measuring ZK Presentations for Real Credentials (JWT + mDL)

A small Rust lab that vendors microsoft/crescent-credentials, generates Crescent test vectors, and benchmarks zksetup/prove/show/verify across several parameters — including proof sizes and selective disclosure variants.

Baby-Ligero: Three Tiny Tests for a Tiny Circuit — ZK Hack S3M5

A mini Rust lab that implements a baby version of Ligero's three tests — proximity, multiplication, and linear — for a tiny arithmetic circuit, and uses them to see soundness amplification in action.

SIS Labs — Commitments, PoK & MC soundness experiment (ZK Hack S3M3)

From Vadim Lyubashevsky's lattice-based SNARKs whiteboard to a tiny Rust lab: SIS commitments, a proof of knowledge, and a soundness experiment.