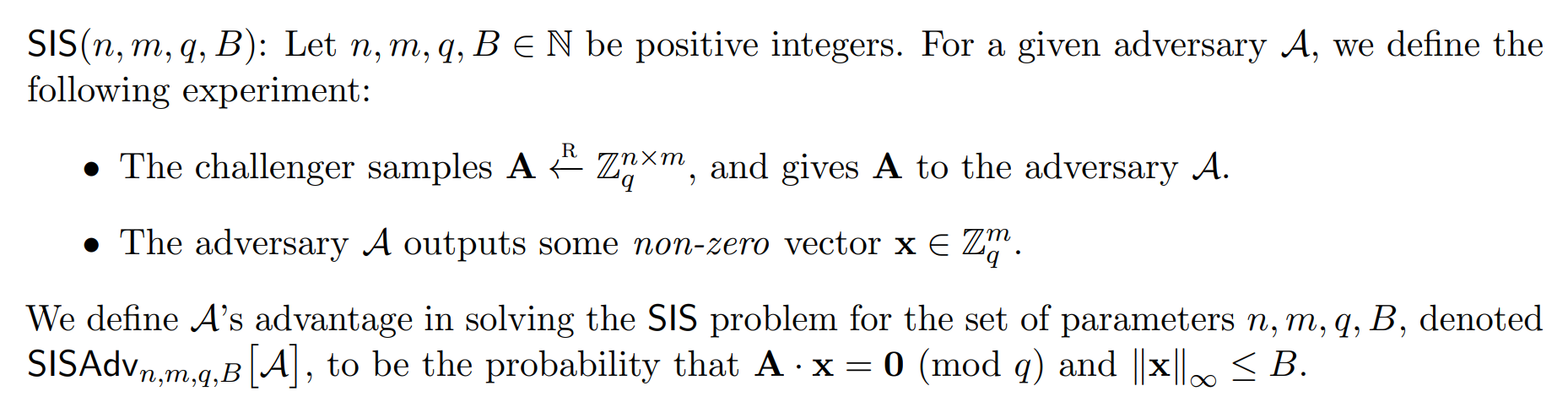

SIS Labs — Commitments, PoK & MC soundness experiment (ZK Hack S3M3)

TL;DR — I took the lattice-based SNARKs session from ZK Hack S3M3 and turned the first half of it into a small Rust lab:

Implement a SIS-based commitment .

Brute-force a toy binding attack by searching for another short opening.

Build a 3-move sigma protocol (proof of knowledge of ).

Run a Monte Carlo soundness experiment and see the cheating probability decay like .

All the code lives in github.com/reymom/sis-labs.

1. Motivation — from ZK Hack whiteboard to Rust code

In ZK Hack S3M3, Vadim Lyubashevsky and Nicolas Mohnblatt walk through how to build lattice-based SNARKs from SIS (Short Integer Solution)–style problems. The whiteboard is dense:

- SIS hardness,

- commitments from SIS,

- proving knowledge of a short vector,

- proving norms of vectors using the left–right technique,

- finally moving from integers to polynomial rings for efficiency.

That's a lot to digest in one sitting.

My goal here is to lock in intuition by coding a tiny, very non-production, SIS lab:

- Define SIS and “short vectors”.

- Build a simple SIS commitment in Rust.

- Try to break binding with a naive brute-force.

- Implement a proof of knowledge (sigma protocol).

- Run a soundness experiment and compare to the theoretical bound

Sketch where this grows into real lattice-based SNARKs (matrix challenges, left–right, ring-SIS).

If you want the references first, here's the reading list:

- ZK Hack S3M3 — Lattice-based SNARKs

- Lecture 9: Lattice Cryptography and the SIS Problem

- Generating hard instances of lattice problems, by Miklós Ajtai

- Optional — LaBRADOR: Compact Proofs for R1CS from Module-SIS

2. SIS basics

We work over the ring , integers modulo a small prime .

SIS, in its basic form:

Given a random matrix , find a non-zero short vector such that:

“Short” usually means a bounded norm. In this lab we use:

- entries in ,

- the infinity norm .

SIS is believed to be hard even for quantum computers. Binding for commitments and soundness for proofs rely on its hardness.

3. Matrix playground

We first define a basic matrix struct to operate mod q.

use rand::{Rng, SeedableRng};

use rand_chacha::ChaCha20Rng;

pub type Matrix = Vec<Vec<i64>>;

pub type Vector = Vec<i64>;

#[derive(Clone)]

pub struct MatParams {

pub n: usize,

pub m: usize,

pub q: i64,

}

pub fn sample_matrix(p: &MatParams, rng: &mut ChaCha20Rng) -> Matrix {

(0..p.n)

.map(|_| {

(0..p.m)

.map(|_| rng.gen_range(0..p.q))

.collect()

})

.collect()

}

pub fn mul_mod(p: &MatParams, a: &Matrix, s: &Vector) -> Vector {

a.iter()

.map(|row| {

let v = row.iter()

.zip(s)

.map(|(ai, si)| ai * si)

.sum::<i64>();

v.rem_euclid(p.q)

})

.collect()

}We use

ChaCha20Rng: a cryptographically secure random number generator that uses the ChaCha algorithm. ChaCha is a stream cipher designed by Daniel J. Bernstein, that we use as an RNG. It is an improved variant of the Salsa20 cipher family, which was selected as one of the "stream ciphers suitable for widespread adoption" by eSTREAM.

4. SIS helpers: short vectors and a toy binding attack

We then implement short vectors and toy binding attack:

pub fn sample_short_vector(m: usize, rng: &mut ChaCha20Rng) -> Vec<i64> {

(0..m).map(|_| rng.random_range(-1..=1)).collect()

}

pub fn norm_inf(v: &[i64]) -> i64 {

v.iter().map(|x| x.abs()).max().unwrap()

}

pub fn try_break_binding(

a: &[Vec<i64>],

t: &[i64],

q: i64,

iterations: u64,

rng: &mut ChaCha20Rng,

) -> Option<Vec<i64>> {

let m = a[0].len();

for _ in 0..iterations {

// try random short vector

let cand: Vec<i64> = (0..m).map(|_| rng.random_range(-1..=1)).collect();

let tcand: Vec<i64> = a

.iter()

.map(|row| row.iter().zip(&cand).map(|(ai, si)| ai * si).sum::<i64>() % q)

.collect();

if tcand == t {

return Some(cand);

}

}

None

}1. norm_inf — what is it, and why does SIS care?

For a vector the is:

It measures only the largest absolute coordinate. We use this for:

- check our sampled

sis “short” (entries in{−1,0,1}) - check if a malicious alternative opening

s'is still “short” - evaluate binding: if you find a second opening

s'that is also “short”, commitment breaks.

This matches exactly Vadim's talk: the binding property reduces to finding a small solution to SIS, which should be infeasible.

2. try_break_binding — what is it doing?

Given the commitment:

A cheating prover wants to find another opening (also short!).

That's exactly searching for a collision in the commitment:

We don't do smart algebra; we brute-force:

- Sample many short vectors

- Compute

- Check whether it matches the original commitment

Since this space is tiny (), we might find collisions when:

- small

- small

- is small random matrix

That's expected — this is a toy. This teaches us:

- Binding requires SIS hardness.

- Toy parameters break easily.

- Increasing , , makes collisions extremely unlikely.

- Useful intuition before doing interactive proofs.

5. SIS commitment scheme

Step 1 — Setup

We choose:

- public matrix

- secret short vector

- modulus

This matches the compressing SIS-commitment scheme presented by Vadim.

Step 2 — Commit

Compute:

The pair (A, t) is public; s is the opening.

Step 3 — Verify Opening

Verifier checks:

If true, the commitment opens correctly.

Is it secure?

- Hiding: small-domain hiding (not statistically perfect, but OK for demos).

- Binding: finding another short

s'with the sametreduces to SIS and is believed hard.

pub struct Commitment {

pub t: Vector,

}

pub fn commit(p: &MatParams, a: &Matrix, s: &Vector) -> Commitment {

let t = mul_mod(p, a, s);

Commitment { t }

}

pub fn open(p: &MatParams, a: &Matrix, s: &Vector, c: &Commitment) -> bool {

mul_mod(p, a, s) == c.t

}

pub fn print_commit_info(s: &Vector, t: &Vector) {

println!("Opening vector s: {:?}", s);

println!("||s||_∞ = {}", norm_inf(s));

println!("Commitment t: {:?}", t);

}6. Experiment: commitment + toy binding attack

We start with a simple experiment to check the commitment and try a simple break binding:

use crate::commit::{commit, open, print_commit_info};

use crate::matrix::{MatParams, sample_matrix};

use crate::sis::{sample_short_vector, try_break_binding};

pub fn run_basic_demo() {

let p = MatParams {

n: 20,

m: 40,

q: 257,

};

let mut rng = ChaCha20Rng::from_rng(&mut rand::rng());

let a = sample_matrix(&p, &mut rng);

let s = sample_short_vector(p.m, &mut rng);

let now = Instant::now();

let c = commit(&p, &a, &s);

let dt = now.elapsed();

println!("Commit computed in {:?}", dt);

print_commit_info(&s, &c.t);

println!("Valid opening? {}", open(&p, &a, &s, &c));

println!("Attempting to break binding...");

let attempt = try_break_binding(&a, &c.t, p.q, 100_000, &mut rng);

match attempt {

Some(s2) => println!("Found second opening: {:?}", s2),

None => println!("No alternative opening found."),

}

}We'll get as expected:

cargo run

Compiling sis-lab v0.1.0 (/home/reymon/Projects/crypto/cryptography/sis-lab)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.20s

Running `target/debug/sis-lab`

Commit computed in 24.287µs

Opening vector s: [0, 1, 1, -1, -1, 1, 1, -1, 1, -1, 0, 0, -1, 0, -1, 0, -1, -1, 1, 0, -1, -1, 1, -1, 0, 1, -1, -1, -1, -1, 0, 0, -1, 0, -1, -1, 0, 0, 1, 0]

||s||_∞ = 1

Commitment t: [88, 157, 3, 251, 111, 230, 127, 49, 210, 223, 65, 242, 231, 101, 168, 98, 205, 103, 88, 16]

Valid opening? true

Attempting to break binding...

No alternative opening found.7. Proof of Knowledge (3-move sigma protocol)

- Commit (Prover → Verifier):

- Prover samples random short .

- Computes .

- Sends .

- Challenge (Verifier → Prover)

- Verifier samples random bit .

- Sends .

- Response (Prover → Verifier)

- If : send .

- If : send .

- Verification

- If :

- Check and that is short.

- If :

- Compute and check:

- Check is short-ish.

- Compute and check:

- If :

In short:

- Verifier randomness forces the prover to “open” either

r(a fresh short vector) orr+s. - If prover could cheat without knowing

s, they’d need to correctly answer both challenges for the sameu, which lets an extractor recoversfrom two transcripts — that’s the usual sigma protocol soundness story.

#[derive(Debug)]

pub struct PoKParams {

/// Maximum allowed infinity-norm for responses (for "shortness")

pub max_norm: i64,

}

#[derive(Debug)]

pub struct PoKTranscript {

pub u: Vector,

pub challenge: u8,

pub response: Vector,

pub accepted: bool,

}

/// Simulate a single sigma-protocol round for proving knowledge of s in t = A*s mod q.

pub fn simulate_pok_round(

p: &MatParams,

a: &Matrix,

t: &Vector,

s: &Vector,

pok: &PoKParams,

rng: &mut ChaCha20Rng,

) -> PoKTranscript {

// Prover's randomness

let r = sample_short_vector(p.m, rng);

let u = mul_mod(p, a, &r);

// Verifier's random challenge bit

let challenge: u8 = rng.random_range(0..=1);

// Prover's response

let (response, accepted) = if challenge == 0 {

// Case b = 0: Prover reveals r

let z = r;

// Verifier checks: A*z == u mod q, and ||z||_inf <= max_norm

let lhs = mul_mod(p, a, &z);

let norm_ok = norm_inf(&z) <= pok.max_norm;

let accepted = lhs == u && norm_ok;

(z, accepted)

} else {

// Case b = 1: Prover reveals r + s

let z: Vector = r.iter().zip(s).map(|(ri, si)| ri + si).collect();

// Verifier checks: A*z == u + t mod q, and ||z||_inf <= max_norm

let lhs = mul_mod(p, a, &z);

let u_plus_t: Vector = u

.iter()

.zip(t)

.map(|(ui, ti)| (ui + ti).rem_euclid(p.q))

.collect();

let norm_ok = norm_inf(&z) <= pok.max_norm;

let accepted = lhs == u_plus_t && norm_ok;

(z, accepted)

};

PoKTranscript {

u,

challenge,

response,

accepted,

}

}

/// Run multiple rounds to see soundness in practice and print a small transcript.

pub fn run_pok_demo(p: &MatParams, a: &Matrix, t: &Vector, s: &Vector, rng: &mut ChaCha20Rng) {

let pok_params = PoKParams { max_norm: 3 }; // allow small but not huge responses

let rounds = 5;

println!("\n=== PoK demo: {} rounds ===", rounds);

for i in 0..rounds {

let tr = simulate_pok_round(p, a, t, s, &pok_params, rng);

println!(

"Round {}: challenge = {}, accepted = {}",

i, tr.challenge, tr.accepted

);

println!(" u = {:?}", tr.u);

println!(" z = {:?}", tr.response);

}

}Adding this PoK demo on top of the same (A, t, s) on top of our previous little experiment we get:

=== PoK demo: 5 rounds ===

Round 0: challenge = 0, accepted = true

Round 1: challenge = 0, accepted = true

Round 2: challenge = 1, accepted = true

Round 3: challenge = 1, accepted = true

Round 4: challenge = 0, accepted = trueSo now we already have done:

- first half = “SIS commitments & binding,”

- second half = “Proof of knowledge for the committed short vector.”

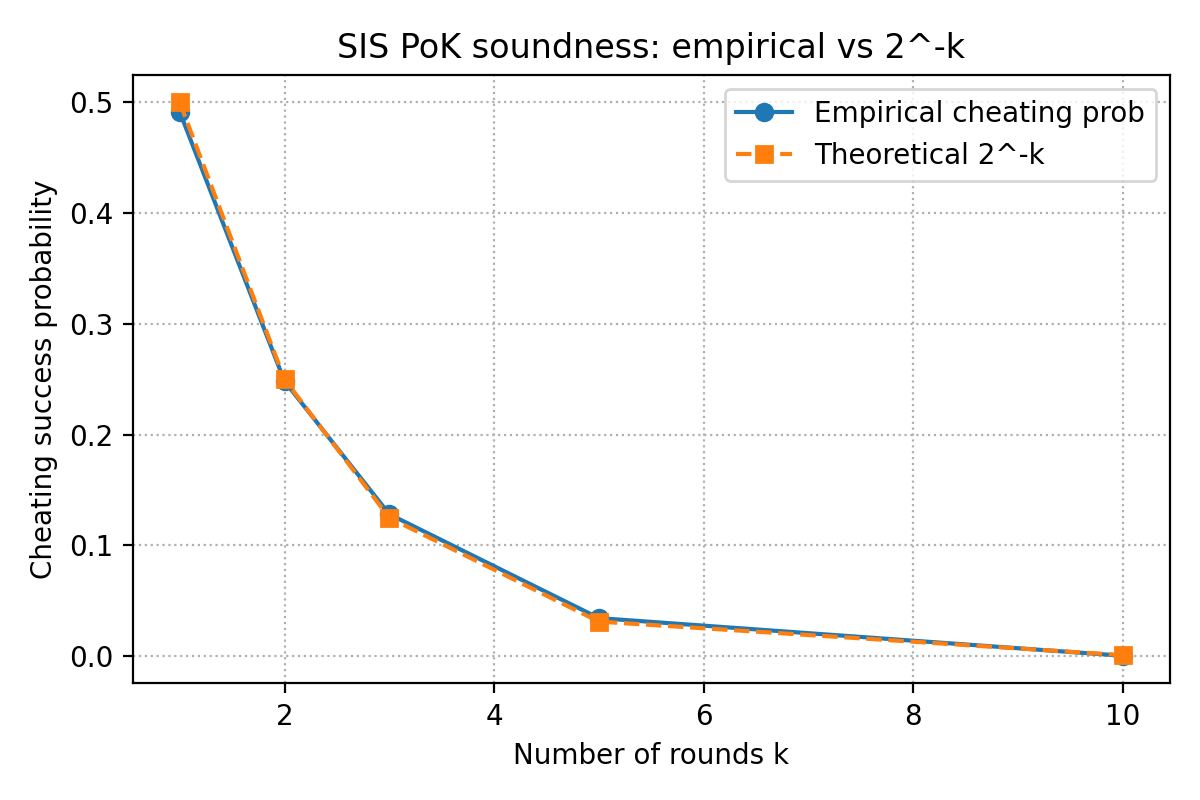

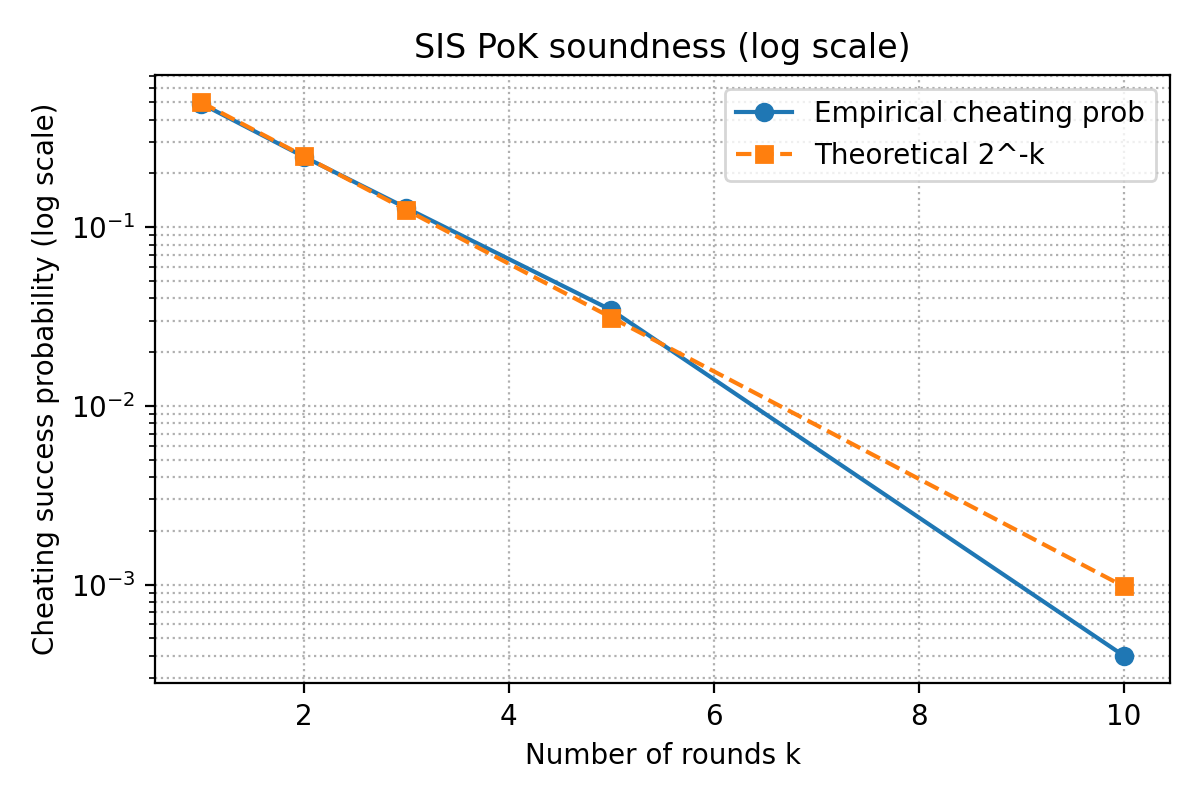

Multi-round soundness: what are we measuring?

We now have a 3-move sigma protocol, where the prover knows a short such that . For each the round, the prover sends and the verifier sends a random bit . Then the prover responds with if , otherwise . Verifier finally checks linear relation and norm bound. If the prover is honest, they always pass. However, if the prover is cheating (does not know ), they cannot prepare openings that satisfy both possible checks for a fixed . Best they can do: prepare to answer only one of the two challenges correctly.

So per round:

- Cheater passes with probability ≈ 1/2.

- After

kindependent rounds, cheater passes all k with probability ≈ .

We'll now:

- Implement a simple cheating prover that only knows how to answer

b = 0. - Run many trials, and estimate empirical success probabilities for

k = 1,2,3,5,10. - Compare to theoretical .

8. Soundness experiment (cheating prover)

Our cheater is intentionally dumb but matches the information-theoretic bound: it only knows how to handle one of the two challenges. That’s enough to see empirical ≈ .

/// Simulates a simple cheating prover that only knows how to answer challenge b = 0.

/// For b = 1, it just reuses the same z, which almost never satisfies the equation.

fn cheating_round(

p: &MatParams,

a: &Matrix,

t: &Vector,

rng: &mut ChaCha20Rng,

) -> bool {

// Cheater picks a random short z and sets u = A*z.

let z = sample_short_vector(p.m, rng);

let u = mul_mod(p, a, &z);

// Verifier samples random challenge bit.

let challenge: u8 = rng.gen_range(0..=1);

// Cheater always responds with the same z, regardless of challenge.

let z_resp = z;

if challenge == 0 {

// Verifier checks: A*z_resp == u

let lhs = mul_mod(p, a, &z_resp);

lhs == u

} else {

// Verifier checks: A*z_resp == u + t (mod q)

let lhs = mul_mod(p, a, &z_resp);

let u_plus_t: Vector = u

.iter()

.zip(t)

.map(|(ui, ti)| (ui + ti).rem_euclid(p.q))

.collect();

lhs == u_plus_t

}

}

/// Run a soundness experiment for several values of k (number of rounds),

/// estimating cheating success probability and comparing to 2^-k.

pub fn run_soundness_analysis(

p: &MatParams,

a: &Matrix,

t: &Vector,

rng: &mut ChaCha20Rng,

) {

// Number of independent repetitions per k.

let trials_per_k: u32 = 5_000;

let ks: [usize; 5] = [1, 2, 3, 5, 10];

println!("\n=== Soundness experiment (cheating prover) ===");

println!("k, empirical_success_prob, theoretical_2^-k");

for &k in &ks {

let mut success_trials: u32 = 0;

for _ in 0..trials_per_k {

// One "attempt" where the cheater faces k rounds in sequence.

let mut all_rounds_accepted = true;

for _round in 0..k {

let accepted = cheating_round(p, a, t, rng);

if !accepted {

all_rounds_accepted = false;

break;

}

}

if all_rounds_accepted {

success_trials += 1;

}

}

let empirical = success_trials as f64 / trials_per_k as f64;

let theoretical = 2f64.powi(-(k as i32));

println!(

"k = {:2}, empirical ≈ {:.6}, theory = {:.6}",

k, empirical, theoretical

);

}

}We will now update our experiment to call the new soundness function.

=== Soundness experiment (cheating prover) ===

k, empirical_success_prob, theoretical_2^-k

k = 1, empirical ≈ 0.491400, theory = 0.500000

k = 2, empirical ≈ 0.248200, theory = 0.250000

k = 3, empirical ≈ 0.128200, theory = 0.125000

k = 5, empirical ≈ 0.034400, theory = 0.031250

k = 10, empirical ≈ 0.000400, theory = 0.000977Despite the tiny sample size (5k trials per k), the empirical curve hugs the theoretical line quite nicely. On a log scale it looks almost perfectly straight.

9. Future directions

So far we stayed in the “toy” regime: small integer matrices, a simple SIS-based commitment, and a sigma protocol that proves “I know a short vector sss such that ” That’s already enough to see the core ideas that show up in lattice-based SNARKs, but the constructions in Vadim’s talk go quite a bit further. Here are three natural directions you could take this codebase next:

- Matrix challenges and linear relations Right now, our proof system only certifies that some short sss exists behind the commitment. In more advanced protocols, you want to prove that sss satisfies additional linear relations: constraints of the form

for some public matrix and vector . The usual trick is to let the verifier send a matrix challenge , and then the prover has to respond with some compressed information like . If the prover can consistently answer for many independent challenges, an extractor (who sees multiple transcripts) can reconstruct and be sure that it really satisfies those linear relations. Conceptually, you move from "I know some short solution" to "I know the specific short solution that satisfies all these linear equations," which is exactly what you need in a SNARK to enforce a circuit's linear constraints.

- Left–right technique for precise norm bounds Our norm checks are very coarse: we just enforce “coordinates not too big” using the -norm. In practice, security often depends on a much more precise bound on (typically an -norm), because that's what connects the protocol back to the underlying SIS hardness assumptions. The "left–right" technique from the talk is a clever way to prove statements like "" or "" while still working with linear objects. Roughly, you randomize and split your vectors into "left" and “right” pieces, and then you use identities of the form

together with random projections to encode this quadratic relation as a collection of linear checks over carefully structured commitments. The end result is that the verifier gains tight control over the norm of the witness, without ever seeing the witness itself.

- From integer SIS to ring-SIS over polynomial rings Everything in this post lives in : plain integer matrices modulo . That's simple to code, but it's not what you'd actually use in a serious lattice-based system. Real-world schemes move to polynomial rings, like:

and work with ring-SIS instead of plain SIS.

Algebraically, you replace "matrix times vector" with "polynomial (or module) multiplication." Algorithmically, that buys you huge efficiency gains: fast multiplication via FFT/NTT, better parameter trade-offs, and much more compact keys and proofs. Conceptually, though, it’s still the same picture: commit to a short element in a lattice-like structure, and prove linear and quadratic relations about it without revealing the element.

All three of these ideas—matrix challenges, left–right norm proofs, and ring-SIS—can be layered on top of the tiny prototype we built here. The code in this post is the “scalar, one-dimensional cartoon” of what actually happens in lattice-based SNARKs; the real constructions are the same story, but with richer algebra and more careful parameter choices.

10. References and further reading

Stay Updated

Get notified when I publish new articles about Web3 development, hackathon experiences, and cryptography insights.

You might also like

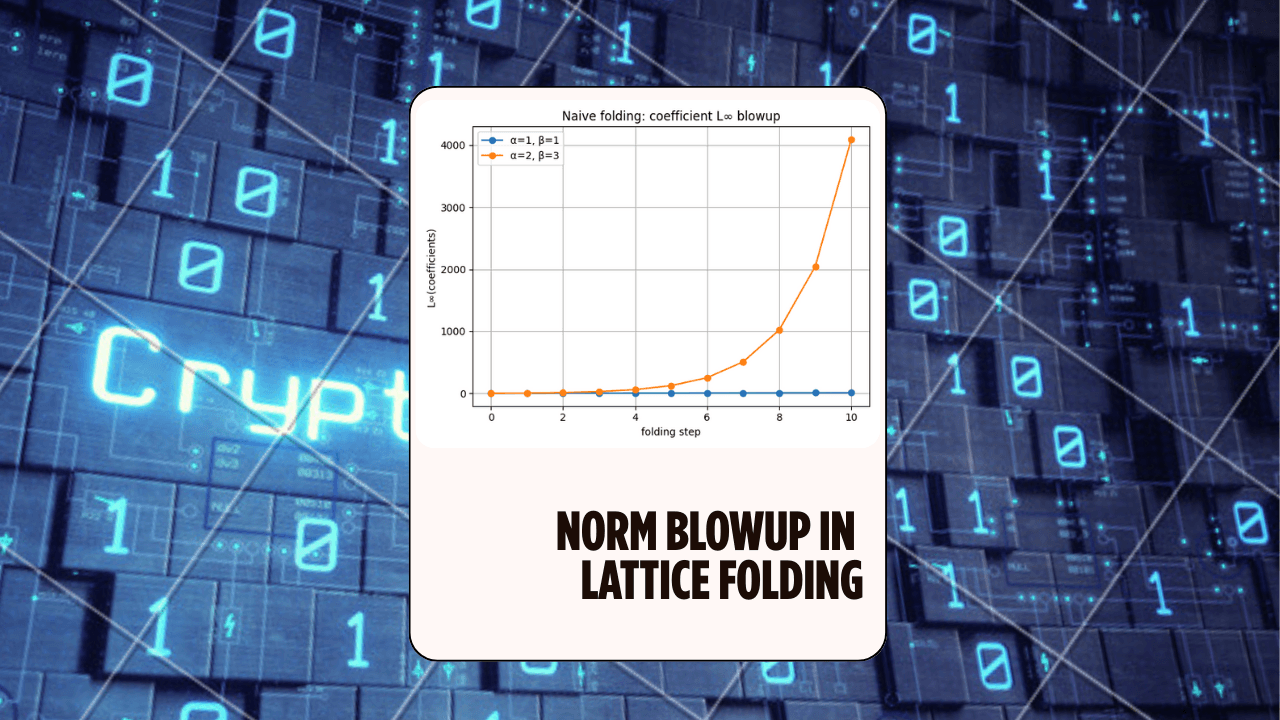

Norm Blowup in Lattice Folding (LatticeFold Lab) — ZK Hack S3M4

A hands-on Rust experiment exploring why folding causes norm blowup in lattice commitments, and how decomposition keeps the digits small — the core idea behind LatticeFold and LatticeFold+.

NTT Bench — BabyBear vs Goldilocks (ZK Hack S3M2)

Hands-on NTT benchmarks over BabyBear and Goldilocks fields, connecting Jim Posen’s ZK Hack talk on high-performance SNARK/STARK engineering to real Rust code.

ZKML EZKL MNIST Lab: Verifiable Inference, Quantization, and the Prover Memory Wall

A small, reproducible ZKML lab: train a CNN, export ONNX, compile an EZKL circuit, generate keys, prove & verify inference — then benchmark the practical tradeoff that matters on consumer hardware: numerical fidelity vs prover memory / PK size.