Baby-Ligero: Three Tiny Tests for a Tiny Circuit — ZK Hack S3M5

TL;DR — I took Muthu Venkitasubramaniam's Ligero whiteboard session (ZK Hack S3M5) and distilled the core idea into a tiny Rust lab:

- Encode a toy circuit z = x * y + x over a small field.

- Arrange its wires into rows of a matrix U, each row a tiny Reed-Solomon (RS) codeword.

- Implement the three Ligero-style tests on the rows:

- a proximity test that only checks “are you in the code?”,

- a multiplication test that checks t = x*y,

- a linear test that checks z = t + x.

- Craft a cheating strategy that passes proximity + linear, and see empirically that:

- one round of tests catches it with probability ≈ 1/p,

- repeating with fresh randomness drives cheating probability down like ≈ (1/p)^k.

All the code built for this study session can be found on github: ligero-mini-lab.

1. Motivation

In week 5 of my ZK learning plan (following the ZK Hack Whiteboard Sessions), I watched Muthu Venkitasubramaniam explain Ligero. The part that really grabbed me:

- Ligero is not "just another polynomial-commitment SNARK".

- It comes from the MPC-in-the-head paradigm, but what you actually see in the protocol are:

- a big matrix U of codewords (rows),

- three simple tests defined as random linear combinations of those rows:

- proximity (are you close to a code?),

- multiplication (are the products consistent?),

- linear (do linear constraints hold?).

He claims that if you understand this U + tests picture, you're basically one step away from a full zero-knowledge SNARK with succinct verification.

So my goal for this week was:

Build a baby Ligero in Rust that actually runs those three tests on a tiny circuit, and see soundness amplification in numbers.

No MPC, no full pre-processing SNARK — just enough structure to internalize what those three tests are really doing.

2. From Ligero to a Baby Model

In the talk, Muthu considers a vector witness

- with ,

- and constraints of the form (coordinate-wise multiplication).

He then packs everything into a matrix U with 3m rows, each row a vector u_i ∈ F^n that lives in a linear code (think Reed-Solomon).

On this U, he defines three tests with a random challenge r:

-

Proximity test:

where the weight vector is .The verifier checks that “reconstructs correctly” as a codeword (low-degree polynomial) → proximity to RS code.

-

Multiplication test:

.Each triple encodes ; the test checks all at once.

-

Linear test:

where .This enforces the linear constraints on the encoded rows.

My "baby Ligero" does a tiny version of this:

- I pick a small prime field with

p = 97. - I pick very small parameters:

m= number of “gates” / coordinates (e.g. 4),n= codeword length (e.g. 7).

- I build a matrix

Uwhose rows are RS codewords (evaluations of low-degree polynomials). - I implement:

- a proximity test with

V_p, - a multiplication test with

V_m, - a linear test for a specific constraint.

- a proximity test with

Then I simulate an honest prover and a clever cheating prover and watch the tests behave.

3. Tiny Field and Reed-Solomon Machinery

3.1 Field with a Small Prime

For this lab I use a small prime modulus p = 97, mainly so I can debug by eye:

/// Small prime field F_p used throughout the Ligero mini lab.

#[derive(Copy, Clone, Debug, PartialEq, Eq, Hash)]

pub struct F {

/// Always kept reduced modulo P.

pub const P: u32 = 97;

value: u32,

}

impl F {

pub fn from(x: u32) -> Self {

Self { value: x % Self::P }

}

pub fn as_u32(self) -> u32 {

self.value

}

pub fn pow(self, mut exp: u64) -> F {

let mut base = self;

let mut acc = F::from(1);

while exp > 0 {

if exp & 1 == 1 {

acc = acc * base;

}

base = base * base;

exp >>= 1;

}

acc

}

pub fn inv(self) -> F {

assert!(self.value != 0, "no inverse for 0");

// Extended Euclidean algorithm returns s such that s * self ≡ 1 (mod P).

eea_inv(self)

}

}The inverse uses the Extended Euclidean Algorithm (EEA):

- Standard Euclidean algorithm computes

gcd(a, p)via repeated remainders. - EEA also tracks coefficients

s, twith: - Over a prime field,

gcd(a,p)=1for any non-zeroa, so: andsis the modular inverse ofa.

So F::inv is literally "EEA on a and p, return the s".

3.2 Reed–Solomon: Evaluate / Interpolate / Low-degree Check

I fix a tiny RS domain:

pub struct Domain {

pub points: Vec<F>,

}

impl Domain {

pub fn new_n(n: usize) -> Self {

// α_j = j for j=0..n-1 in F_p

let points = (0..n).map(|j| F::from(j as u32)).collect();

Self { points }

}

pub fn len(&self) -> usize {

self.points.len()

}

}Then three basic operations:

- Evaluate a polynomial on the domain:

pub fn eval_poly(coeffs: &[F], domain: &Domain) -> Vec<F> {

domain.points.iter().map(|&x| {

let mut acc = F::from(0);

let mut power = F::from(1);

for &c in coeffs {

acc = acc + c * power;

power = power * x;

}

acc

}).collect()

}- Interpolate a polynomial of degree

< deg_boundfrom evaluations (or returnNoneif inconsistent):

pub fn interpolate_poly(values: &[F], domain: &Domain, deg_bound: usize) -> Option<Vec<F>> {

let n = domain.len();

if deg_bound >= n {

return None; // cannot uniquely interpolate

}

// Solve Vandermonde system for coefficients c_0..c_deg_bound

// If there's a unique solution, return it; otherwise None.

// (I use a simple Gaussian elimination in the lab.)

// ...

}- Low-degree test: "Is this vector a codeword of degree < deg_bound?":

pub fn is_low_degree(codeword: &[F], domain: &Domain, deg_bound: usize) -> bool {

if let Some(coeffs) = interpolate_poly(codeword, domain, deg_bound) {

// Re-evaluate and check it matches exactly

let roundtrip = eval_poly(&coeffs, domain);

roundtrip == codeword

} else {

false

}

}Intuition:

- An RS codeword is just "evaluation of a low-degree polynomial on a fixed domain".

- If a vector passes

is_low_degree, it lies on the code (not necessarily close — my lab is stricter than the real thing, which allows small errors). - Ligero uses this to express “U is close to a code” via random linear combinations.

In my baby setting, proximity = "exact RS codeword", because I want to see the tests clearly, not deal with noise.

4. Building the Tableau for a Single Gate

Start with a tiny circuit:

I introduce an intermediate wire so I can separate non-linear and linear parts:

- multiplicative constraint:

t = x*y, - linear constraint:

z = t + x.

4.1 Witness and Parameters

/// Witness for z = x*y + x in F_p.

#[derive(Clone, Debug)]

pub struct Witness {

pub x: F,

pub y: F,

pub z: F,

}

impl Witness {

pub fn new(x: u32, y: u32) -> Self {

let x_f = F::from(x);

let y_f = F::from(y);

let z_f = x_f * y_f + x_f;

Self { x: x_f, y: y_f, z: z_f }

}

}

#[derive(Clone, Debug)]

pub struct LigeroParams {

pub m: usize, // number of multiplication gates

pub n: usize, // codeword length

pub deg_bound: usize, // degree bound for each row polynomial

}

#[derive(Clone, Debug)]

pub struct Row {

pub values: Vec<F>, // one RS codeword

}

#[derive(Clone, Debug)]

pub struct Tableau {

pub params: LigeroParams,

pub domain: Domain,

pub rows: Vec<Row>, // rows = 4m: x, y, t, z per gate

}4.2 Honest Tableau for m = 1

For one gate, I use four rows:

u_0= encoding ofx,u_1= encoding ofy,u_2= encoding oft = x*y,u_3= encoding ofz.

Each row is the evaluation of a constant polynomial (degree 0): f_x(t) = x, etc.

impl Tableau {

/// Build an honest tableau for a single gate z = x*y + x.

pub fn from_witness_single_gate(w: &Witness, params: LigeroParams) -> Self {

assert_eq!(params.m, 1, "from_witness_single_gate assumes m = 1");

let domain = Domain::new_n(params.n);

let x = w.x;

let y = w.y;

let t = x * y;

let z = w.z;

let fx = [x];

let fy = [y];

let ft = [t];

let fz = [z];

let row_x = Row { values: eval_poly(&fx, &domain) };

let row_y = Row { values: eval_poly(&fy, &domain) };

let row_t = Row { values: eval_poly(&ft, &domain) };

let row_z = Row { values: eval_poly(&fz, &domain) };

Tableau {

params,

domain,

rows: vec![row_x, row_y, row_t, row_z],

}

}

}A tiny smoke test:

fn main() {

let w = Witness::new(2, 3); // z = 2*3 + 2 = 8

let params = LigeroParams { m: 1, n: 5, deg_bound: 1 };

let tab = Tableau::from_witness_single_gate(&w, params);

println!("Tableau rows: {:?}", tab.rows);

let r = F::from(42);

println!("Proximity test (V_p low-deg?): {}", tab.proximity_test(r));

println!("Multiplication test (V_m = 0?): {}", tab.multiplication_test(r));

println!("Linear test (constraint holds?): {}", tab.linear_test(r));

}Output:

Tableau rows: [

Row { values: [2, 2, 2, 2, 2] },

Row { values: [3, 3, 3, 3, 3] },

Row { values: [6, 6, 6, 6, 6] },

Row { values: [8, 8, 8, 8, 8] },

]

Proximity test (V_p low-deg?): true

Multiplication test (V_m = 0?): true

Linear test (constraint holds?): trueEvery row is a constant RS codeword, and all constraints hold. Good.

5. The Three Tests on the Rows of U

Now the fun part. I implement three tests on the rows, mirroring the whiteboard formulas, but adapted to my 4-rows-per-gate layout.

Proximity Test

Definition:

- Form a random linear combination of rows:

- Check: is

V_pa low-degree RS codeword?

Code:

impl Tableau {

/// V_p = (1, r, r², ..., r^{rows-1}) · U

/// Check: is V_p a low-degree (< deg_bound) RS codeword?

pub fn proximity_test(&self, r: F) -> bool {

let n = self.domain.len();

let mut v_p = vec![F::from(0); n];

// For each column j, take a random linear combination of row values.

for j in 0..n {

let mut sum = F::from(0);

let mut power = F::from(1); // r^0, r^1, ...

for row in &self.rows {

sum = sum + row.values[j] * power;

power = power * r;

}

v_p[j] = sum;

}

is_low_degree(&v_p, &self.domain, self.params.deg_bound)

}

}Intuition:

- This test only sees code structure. It does not know whether

z = x*y + xholds. - In my toy, both honest and cheating provers keep rows as constant polynomials, so they always pass proximity — by design.

Multiplication Test

For m gates, with row layout [x_i, y_i, t_i, z_i] per gate i, I define:

and require to be identically zero.

impl Tableau {

/// Multiplication test: checks all gates satisfy t_i = x_i * y_i.

pub fn multiplication_test(&self, r: F) -> bool {

let m = self.params.m;

let n = self.domain.len();

let mut v_m = vec![F::from(0); n];

for j in 0..n {

let mut sum = F::from(0);

let mut power = F::from(1); // r^0, r^1, ...

for gate in 0..m {

let idx_x = 4 * gate;

let idx_y = 4 * gate + 1;

let idx_t = 4 * gate + 2;

let xj = self.rows[idx_x].values[j];

let yj = self.rows[idx_y].values[j];

let tj = self.rows[idx_t].values[j];

let diff = xj * yj - tj;

sum = sum + power * diff;

power = power * r;

}

v_m[j] = sum;

}

v_m.iter().all(|&v| v == F::from(0))

}

}- If every gate satisfies

t_i = x_i*y_i, then every diff is zero andV_mis identically zero. - If some gate cheats on the product,

V_mbecomes a non-zero polynomial inr, and only a small fraction ofrmake it vanish.

5.3 Linear Test

I separate the linear part of the constraint:

So I define:

and again require it to be identically zero:

impl Tableau {

/// Linear test: checks all gates satisfy z_i = t_i + x_i.

pub fn linear_test(&self, r: F) -> bool {

let m = self.params.m;

let n = self.domain.len();

let mut v_l = vec![F::from(0); n];

for j in 0..n {

let mut sum = F::from(0);

let mut power = F::from(1);

for gate in 0..m {

let idx_x = 4 * gate;

let idx_t = 4 * gate + 2;

let idx_z = 4 * gate + 3;

let xj = self.rows[idx_x].values[j];

let tj = self.rows[idx_t].values[j];

let zj = self.rows[idx_z].values[j];

let diff = zj - tj - xj; // z - t - x = 0

sum = sum + power * diff;

power = power * r;

}

v_l[j] = sum;

}

v_l.iter().all(|&v| v == F::from(0))

}

}Now:

- Multiplication test checks the non-linear part:

t = x*y. - Linear test checks the linear part:

z = t + x. - Proximity ensures the rows still look like proper codewords.

For m=1, you can already see how they separate concerns: change z and keep t honest, and you'll pass multiplication but fail linear.

6. Extending to Many Gates

To get closer to the talk, I need multiple coordinates (m > 1). I introduce a vector witness:

/// Vector witness for m gates: z_i should satisfy z_i = x_i * y_i + x_i.

#[derive(Clone, Debug)]

pub struct WitnessVec {

pub xs: Vec<F>,

pub ys: Vec<F>,

pub zs: Vec<F>,

}

impl WitnessVec {

pub fn from_xy(xs: Vec<F>, ys: Vec<F>) -> Self {

assert_eq!(xs.len(), ys.len());

let zs = xs.iter().zip(&ys)

.map(|(&x, &y)| x * y + x)

.collect();

Self { xs, ys, zs }

}

pub fn len(&self) -> usize {

self.xs.len()

}

}And a multi-gate tableau builder:

impl Tableau {

/// Build an honest tableau for m gates using a vector witness.

pub fn from_witness_vec(w: &WitnessVec, params: LigeroParams) -> Self {

assert_eq!(params.m, w.len(), "params.m must match witness length");

let domain = Domain::new_n(params.n);

let mut rows = Vec::with_capacity(4 * params.m);

for i in 0..params.m {

let x = w.xs[i];

let y = w.ys[i];

let t = x * y;

let z = w.zs[i];

let fx = [x];

let fy = [y];

let ft = [t];

let fz = [z];

rows.push(Row { values: eval_poly(&fx, &domain) });

rows.push(Row { values: eval_poly(&fy, &domain) });

rows.push(Row { values: eval_poly(&ft, &domain) });

rows.push(Row { values: eval_poly(&fz, &domain) });

}

Tableau { params, domain, rows }

}

}The three tests (proximity_test, multiplication_test, linear_test) already iterate over gate in 0..m, so they work unchanged.

7. A Cheating Strategy and Soundness in Numbers

With m > 1, I can finally craft a cheating prover that:

- keeps all rows as valid RS codewords (so proximity passes),

- keeps all linear constraints

z = t + xtrue (so linear passes), but - breaks multiplication

t = x*yon two gates in a correlated way.

7.1 Correlated Cheat across Two Gates

Let's take m = 4 gates, build an honest tableau, and then modify gates 0 and 1:

let m: usize = 4;

let params = LigeroParams { m, n: 7, deg_bound: 1 };

let xs: Vec<F> = (0..m).map(|_| F::from(rng.gen_range(1..F::P))).collect();

let ys: Vec<F> = (0..m).map(|_| F::from(rng.gen_range(1..F::P))).collect();

let w_vec = WitnessVec::from_xy(xs, ys);

let honest_tab = Tableau::from_witness_vec(&w_vec, params.clone());

// Make a cheating tableau

let mut cheat_tab = honest_tab.clone();

let n = cheat_tab.domain.len();

let delta = F::from(1); // non-zero

let idx_t0 = 4 * 0 + 2;

let idx_z0 = 4 * 0 + 3;

let idx_t1 = 4 * 1 + 2;

let idx_z1 = 4 * 1 + 3;

for j in 0..n {

// Gate 0: add delta to t and z -> z0' = t0' + x0 still holds

cheat_tab.rows[idx_t0].values[j] = cheat_tab.rows[idx_t0].values[j] + delta;

cheat_tab.rows[idx_z0].values[j] = cheat_tab.rows[idx_z0].values[j] + delta;

// Gate 1: subtract delta from t and z -> z1' = t1' + x1 still holds

cheat_tab.rows[idx_t1].values[j] = cheat_tab.rows[idx_t1].values[j] - delta;

cheat_tab.rows[idx_z1].values[j] = cheat_tab.rows[idx_z1].values[j] - delta;

}Effect:

- Rows are still constant polynomials (so proximity passes).

- For each gate

i = 0,1, we changedt_iandz_iin sync:t_i' = t_i ± δ,z_i' = z_i ± δ,- so

z_i' = t_i' + x_istill holds (linear test passes).

- But the products are wrong:

- gate 0:

x0*y0 - t0' = -δ, - gate 1:

x1*y1 - t1' = +δ.

- gate 0:

What does the multiplication test see?

For each column j:

So:

V_mis the same non-zero polynomial inrfor every column.- It is zero iff

r = 1. - If

ris uniform inF_p, the cheating prover passes with probability exactly1/p.

This is a perfect little lab example of "soundness by random linear combination".

7.2 Monte-Carlo Experiment

I wrap everything in a main and run a Monte-Carlo:

fn multigate_soundness_experiment() {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let m: usize = 4;

let params = LigeroParams { m, n: 7, deg_bound: 1 };

// Honest witness + tableau

let xs: Vec<F> = (0..m).map(|_| F::from(rng.gen_range(1..F::P))).collect();

let ys: Vec<F> = (0..m).map(|_| F::from(rng.gen_range(1..F::P))).collect();

let w_vec = WitnessVec::from_xy(xs, ys);

let honest_tab = Tableau::from_witness_vec(&w_vec, params.clone());

// Cheating tableau as above...

let mut cheat_tab = honest_tab.clone();

// apply correlated delta tweak...

// Single r sanity check

let r_test = F::from(42);

println!(

"Honest (single r): prox={}, mult={}, lin={}",

honest_tab.proximity_test(r_test),

honest_tab.multiplication_test(r_test),

honest_tab.linear_test(r_test),

);

println!(

"Cheat (single r): prox={}, mult={}, lin={}",

cheat_tab.proximity_test(r_test),

cheat_tab.multiplication_test(r_test),

cheat_tab.linear_test(r_test),

);

// Monte-Carlo over rounds

let trials = 5_000;

let rounds_list = [1usize, 2, 3];

println!("\nEstimating acceptance probabilities over {trials} trials:");

for rounds in rounds_list {

let mut honest_accept = 0usize;

let mut cheat_accept = 0usize;

for _ in 0..trials {

let mut honest_ok = true;

let mut cheat_ok = true;

for _ in 0..rounds {

let r = F::from(rng.gen_range(0..F::P));

let honest_round = honest_tab.proximity_test(r)

&& honest_tab.multiplication_test(r)

&& honest_tab.linear_test(r);

let cheat_round = cheat_tab.proximity_test(r)

&& cheat_tab.multiplication_test(r)

&& cheat_tab.linear_test(r);

honest_ok &= honest_round;

cheat_ok &= cheat_round;

}

if honest_ok { honest_accept += 1; }

if cheat_ok { cheat_accept += 1; }

}

let honest_rate = honest_accept as f64 / trials as f64;

let cheat_rate = cheat_accept as f64 / trials as f64;

println!(

" rounds = {rounds}: honest_accept ≈ {:.4}, cheat_accept ≈ {:.6}",

honest_rate, cheat_rate

);

}

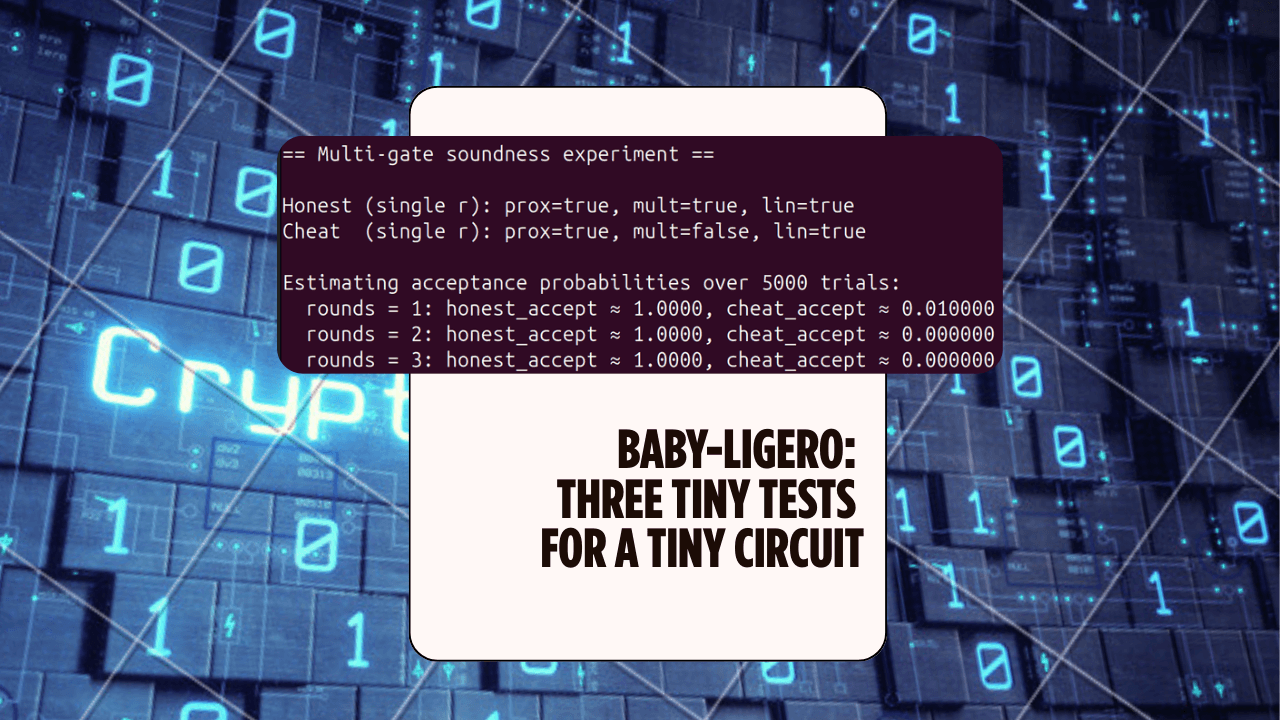

}Running:

Honest (single r): prox=true, mult=true, lin=true

Cheat (single r): prox=true, mult=false, lin=true

Estimating acceptance probabilities over 5000 trials:

rounds = 1: honest_accept ≈ 1.0000, cheat_accept ≈ 0.008600

rounds = 2: honest_accept ≈ 1.0000, cheat_accept ≈ 0.000000

rounds = 3: honest_accept ≈ 1.0000, cheat_accept ≈ 0.000000Interpretation:

- Honest prover passes essentially always (up to floating noise).

- Cheater passes about

0.0086 ≈ 1/116in one round; withp=97and tiny sample size, that's aligned with the theory “≈ 1/p”. - With two independent rounds, cheat acceptance drops to “essentially zero” in 5000 trials — consistent with “probability ≈ 1/p²”.

This is exactly the “soundness amplification” story Muthu tells on the board, but now I've seen it numerically.

8. How This Relates to Real Ligero

My baby lab does capture the idea of a big matrix U whose rows are codewords, as well as the three tests as random linear combinations of those rows:

V_pchecks code structure (proximity).V_mchecks multiplicative constraints.V_ℓchecks linear constraints.

It then also captures the soundness pattern: if a prover cheats but stays in the code and preserves linear constraints, the violation shows up as a non-zero polynomial in r; hitting zero by chance has probability ≈ 1/|F| per round.

It does not yet capture:

- The full MPC-in-the-head construction and how you get

Ufrom secure computation views. - Packed secret sharing over larger blocks and how that interacts with RS codes.

- The full constraint system

A w = band the exacthat_rconstruction. - Pre-processing SNARK aspects (structured reference strings, etc.).

- Real-world parameter choices, noise, and “proximity” vs exact code membership.

But as a mental model, I find this baby lab very effective:

Ligero = "rows in a code + three simple random tests over those rows".

Once we've implemented those three pieces for a toy circuit, the whiteboard becomes much easier to parse.

9. References and Further Reading

- Talk — ZK Hack S3M5: The Ligero Proof System, w/ Muthu Venkitasubramaniam

- Paper — Ligero: Lightweight Sublinear Arguments Without a Trusted Setup (Ames–Hazay–Ishai–Venkitasubramaniam, 2022), ePrint 2022/1608.

- Background on MPC & ZK:

- Zero-Knowledge from Secure Multiparty Computation — Ishai, Kushilevitz, Ostrovsky, Sahai (2007).

- Yuval Ishai, Introduction to Secure Multi-Party Computation (BIU Winter School 2020).

- Polynomial commitments inspired by Ligero:

- Ligerito: A Small and Concretely Fast Polynomial Commitment Scheme — Novakovic, Angeris, 2025, ePrint 2025/1187.

Stay Updated

Get notified when I publish new articles about Web3 development, hackathon experiences, and cryptography insights.

You might also like

Crescent Bench Lab: Measuring ZK Presentations for Real Credentials (JWT + mDL)

A small Rust lab that vendors microsoft/crescent-credentials, generates Crescent test vectors, and benchmarks zksetup/prove/show/verify across several parameters — including proof sizes and selective disclosure variants.

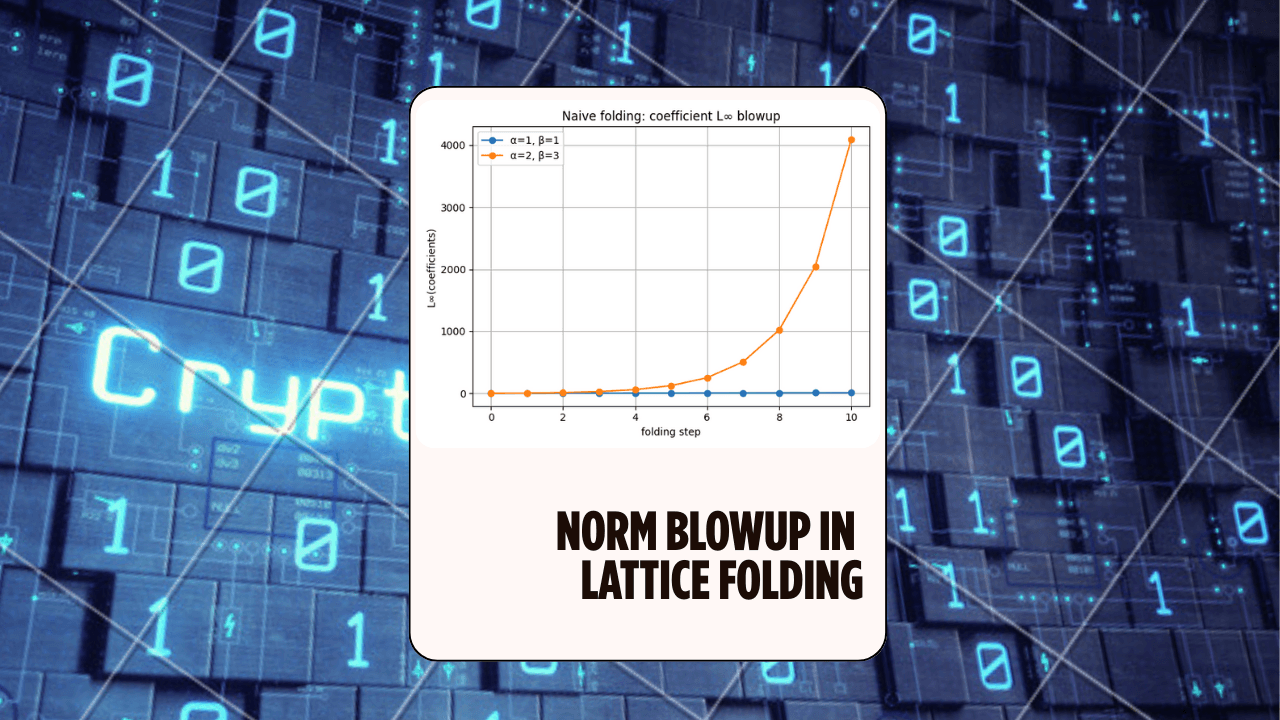

Norm Blowup in Lattice Folding (LatticeFold Lab) — ZK Hack S3M4

A hands-on Rust experiment exploring why folding causes norm blowup in lattice commitments, and how decomposition keeps the digits small — the core idea behind LatticeFold and LatticeFold+.

NTT Bench — BabyBear vs Goldilocks (ZK Hack S3M2)

Hands-on NTT benchmarks over BabyBear and Goldilocks fields, connecting Jim Posen’s ZK Hack talk on high-performance SNARK/STARK engineering to real Rust code.